Twin elements point to the mystery of continents

In the past several years, my most visited states in the US are Arizona and California. During my dozens of flights across the western US, I liked to stare at the vast mountainous lands through the airplane windows.

It was fascinating. Wild, primitive, barren and lonely. The photo below was taken on one of my fights to California. In this photo, the reader can probably see many signs of river washout in these mountainous areas. There were probably more mountains on the continents.

Fig. 1. View of western US from airplane. I took this photo on one of my flights to California.

Why are there so many mountains on the continents?

A little more than two years ago, I came to Rice University to continue my research on Earth’s continents. I was offered a set of very special samples. These rocks are from 50-80 km beneath the surface, and are probably the deepest crustal rocks that humanity can ever get. Up to now, the Kola Superdeep Borehole, drilled by the Soviet Union, still holds the record of deepest artificial point on Earth (12.262 km). So obviously, these rocks were not dug up by human. They were brought to the surface through some violent volcanic eruptions. Our samples are from central Arizona. They are composed of various minerals that crystalized from mantle magmas as they just rose into the crust. In geology, this type of rock is called cumulate.

Fig. 2. Superstructure of the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia, 2007. Today, Kola Superdeep Borehole still represents the deepest artificial point. Image from Wikipedia.

Although cumulates are usually deep seated, crustal cumulates from this deep are scarce. 50-80 km is about twice that of the average continental crust thickness. This is very unusual, and only the crust beneath the highest mountains can be built up to this thickness. Every piece of rock has its story. What can we learn from these rocks from the deepest crust?

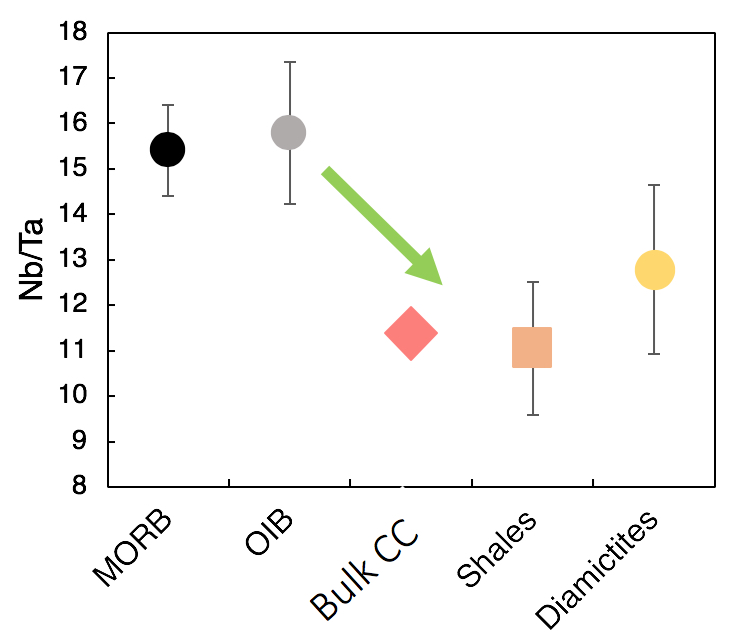

Niobium (Nb) and Tantalum (Ta) are probably unfamiliar to most people, but geochemists have a strong passion about them. They are two metal elements, buried deep in the periodic table. Nb and Ta are very rare in Earth’s crust, a few parts per million or less. They have almost identical chemical properties and behave in pretty much the same ways in most geological processes. Their ratio is constant in Earth’s mantle and the magmas that come from the mantle. When there is more Nb, there is more Ta; when there is less Nb, there is less Ta too. They are twins.

Geologists have long noticed that the ratio of these twin elements is a little different in Earth’s continental crust—Nb is off—it’s lower than it should be. The twins are now separated with some of the Nb being missing in the continental crust.

Fig. 3. The twin element ratio Nb/Ta in Earth’s mantle and continental crust. The mantle Nb/Ta is measured by oceanic basalts (MORB and OIB). These basalts set the reference line. The continental crust Nb/Ta is shown in three ways. One is the model composition (Bulk CC) from my Ph.D. advisor Roberta Rudnick’s famous paper on Treatise on Geochemistry. The other two datapoints represent the average Nb/Ta in shales and diamictites. Geologists use these two types of terrigenous sedimentary rocks to obtain the average composition of the upper continental crust.

Who could have separated Nb from its twin element Ta, and where did the missing Nb go? The missing Nb has been a mystery in Earth’s science, and for decades, geologists have been searching for this missing Nb.

The missing Nb presents a mass non-conservation problem, meaning that some important linkages in the chain of continent formation are missing. The missing Nb could be stored in a hidden crust in the deep Earth. We can’t see and know very little about this crust, but it must have been generated together with the continents. This hidden crust is a dance partner of the continental crust.

Is it possible that our Arizona cumulates tapped this deep hidden crust? We can test this by measuring the twin elements and see if there is an excess of Nb.

I sent the samples to my collaborator, Kang Chen, in China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. He did the painstaking analyses of Nb and Ta compositions in these rocks. While waiting for the results, I surveyed the GeoRoc online database for global rock geochemistry, hoping to find something interesting. I was looking at the compositions of rocks from global volcanic arcs. Volcanic arcs form at plate boundaries where one plate subducts beneath another. In volcanic arcs, new crust with felsic compositions is being generated today. But surprisingly, not all felsic magmas from volcanic arcs show the missing Nb signature like the continental crust. Actually, it is only in places like Andes in South America where the felsic magmas are consistently depleted in Nb.

Fig. 4. Andes mountains on the west coast of South America. Image from web.

Andes is unique among volcanic arcs today. It has the longest mountain range on Earth, spanning over 7000 km on the west coast of South America. With an average elevation of about 4000 m, lands are extreme in Andes. Ojos del Salado located on the border between Chile and Argentina is the highest elevation volcano in the world (6893 m).

Fig. 5. Ojos Del Saldo volcano in the Andes, with an elevation of 6893 m, is the highest elevation volcano in the world. Image from web.

We know that the basaltic mantle magmas feeding the Andean volcanos have just the perfect Nb/Ta ratio, but after the magmas differentiate in the crust and ultimately make it to the surface, some of the Nb is missing. So, what’s going on in the deep crust beneath the Andes? Unfortunately, We don’t have samples from the deep crust beneath Andes, but the ones from Arizona provide an excellent analogue.

Kang finished the measurements and sent the data to me last spring. The results confirmed our hypothesis—the missing Nb from the continents found! These deepest crustal rocks are exactly the critical missing part of the entire continent jigsaw puzzle.

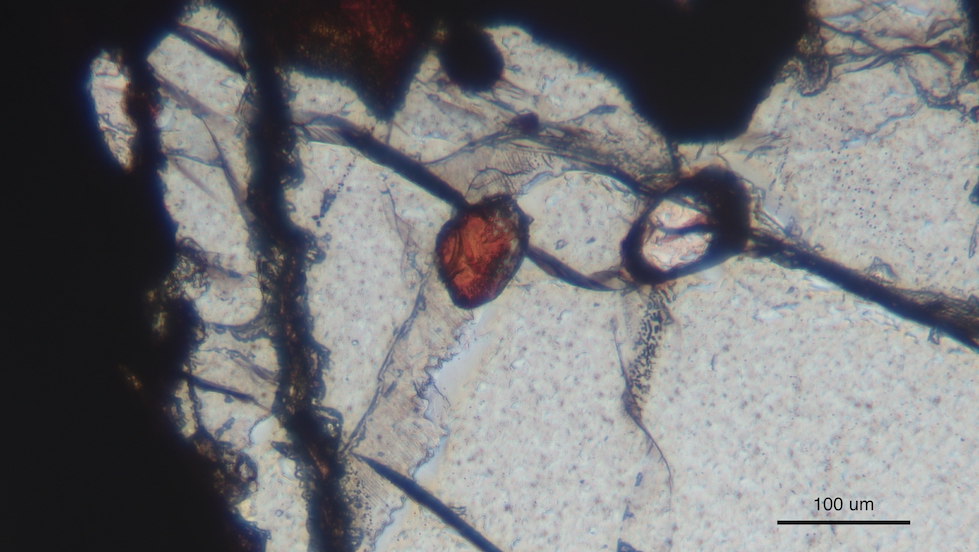

Then a question arises: why would the missing Nb happen only in those extremely mountainous volcanic arcs? In the Arizona cumulates, we found a special mineral—rutile. They are small, only a few tenth of a millimeter. They can only be seen under microscopes. We used a laser ablation technique that allowed us to take samples from very small minerals. Our microanalyses show that rutile is the mineral that can separate Nb from Ta and preferentially grab Nb from magma and put it into its lattice. Rutile is a mineral that we don’t usually see in magmas. It can only crystallize from magmas when the pressure is sufficiently high. After realizing this, everything starts to sort out by itself. It’s only at the roots of giant volcanos where the pressure is great enough to “squeeze” out rutile from magmas.

Fig. 6. A rutile crystal (redish) in our samples. It’s about 80 micron in diameter, a little more the thickness of human hair.

Now the message from the missing Nb is clear: perhaps, just about every piece of the continents was born like the Andes. The lands that we live on, though most of them look flat and peaceful today, all started with massive plateaus and giant volcanos.

Where did the mountains go? After building them, nature stops at nothing to destroy the mountains. Together, erosion, weathering and gravitational collapse conspire to bring mountains down in just a few million years. Rocks are turned into sands, soils and dust. These fine particles travel with rivers and fly with wind, and spread out to the entire world. When these “dirts” dissolve in water, they give off life-essential nutrients that feed microorganisms, then plants, then animals, and all the way up the hierarchy of life. Chemical weathering of the eroded rocks and minerals also consumes the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and ultimately buries it as carbonates in the oceans, which cools off the surface of our planet.

As mountains rise and fall, life prospers.

Fig. 7. I took this photo last year in Tibet as we drove around Yamdrok Lake. In just about every glacial valley, where a stream runs down the mountains, there is a village. Lands are probably more fertile in the valley.