Hunting for the ghost of the recycled lower continental crust

Following the first project, I began to search for this missing lower continental crust in mantle samples with the Eu “probe”. The recycled lower continental crust carries a Eu excess, and any mantle melts that tap this crustal component should show a positive Eu anomaly. In this second project, I looked at mid ocean ridge basalts (MORB), which sample the convecting upper mantle. I analyzed the Eu anomalies in primitive MORB glasses from the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Ocean basins. The results are not straightforward. Most of these primitive MORB samples show weak but significant Eu anomalies, and both positive and negative Eu anomalies are present with a mean value that is statistically indistinguishable from no Eu anomaly.

Does that mean the upper mantle has no Eu anomaly and thus no recycled lower continental crust materials? This is where things become complicated. During mantle partial melting, incompatible elements, such as rare earth elements, prefer the melt phase over the residual solid phases. These elements within the residual minerals diffuse towards the mineral grain boundaries and then enter the melts. Because Eu2+ diffuses more than 10 times faster than Sm3+, Gd3+ and Eu3+, Eu fractionates from Sm and Gd during this process, and the early stage melts will have excess Eu while the late stage melts will have a deficit of Eu because the source minerals are depleted faster in Eu than Sm and Gd. Melts are extracted continuously from the source, and mixing between the melts generated at different stages will create both positive and negative Eu anomalies in the MORB samples.

I approximated these processes with a numerical model, and found that the data match the model reasonably well. Therefore, I proposed that the variation in Eu anomalies in MORB can be explained by kinetic fractionation during mantle partial melting. At this point, I still cannot provide a definitive answer to the question whether the upper mantle hosts recycled lower continental crust. This is because the mantle is such a big reservoir compared with the crust, and even if one puts all of the recycled lower crustal materials into the upper mantle, the induced Eu excess is still small and comparable to the uncertainty of our estimate. But on the other hand, the correlation between Eu anomaly and Pb isotope compositions, another tracer of lower crustal recycling, in ocean island basalts (OIB) led me to suggest a significant amount of the recycled lower crust sank to the OIB source–the lower mantle. Hence, my “best bet”, though it may seem a bit dull, is that the recycled lower crust materials could have mixed into the entire mantle but the lower mantle appears to host much of it.

The reviewing process of this paper was not smooth, and it finally got published months after I graduated, making it the longest project I have worked on. There were debates between the reviewers and us and between reviewers themselves. And after this paper went online, a number of colleagues communicated their own opinions to us, with one coming on the Christmas Eve. For me, this was a learning process because, for the first time, I hit a field with so much debate and perspectives. The second project that gave me similar experiences is the Archean upper crust evolution project, which was eventually published in Science. Through working on these hot topics, I learned how to carry out discussions with people who disagree with me and gain insights from them, how to push our understanding forward, even though I may not be able to solve the problem, and how to feel comfortable in a world of uncertainties.

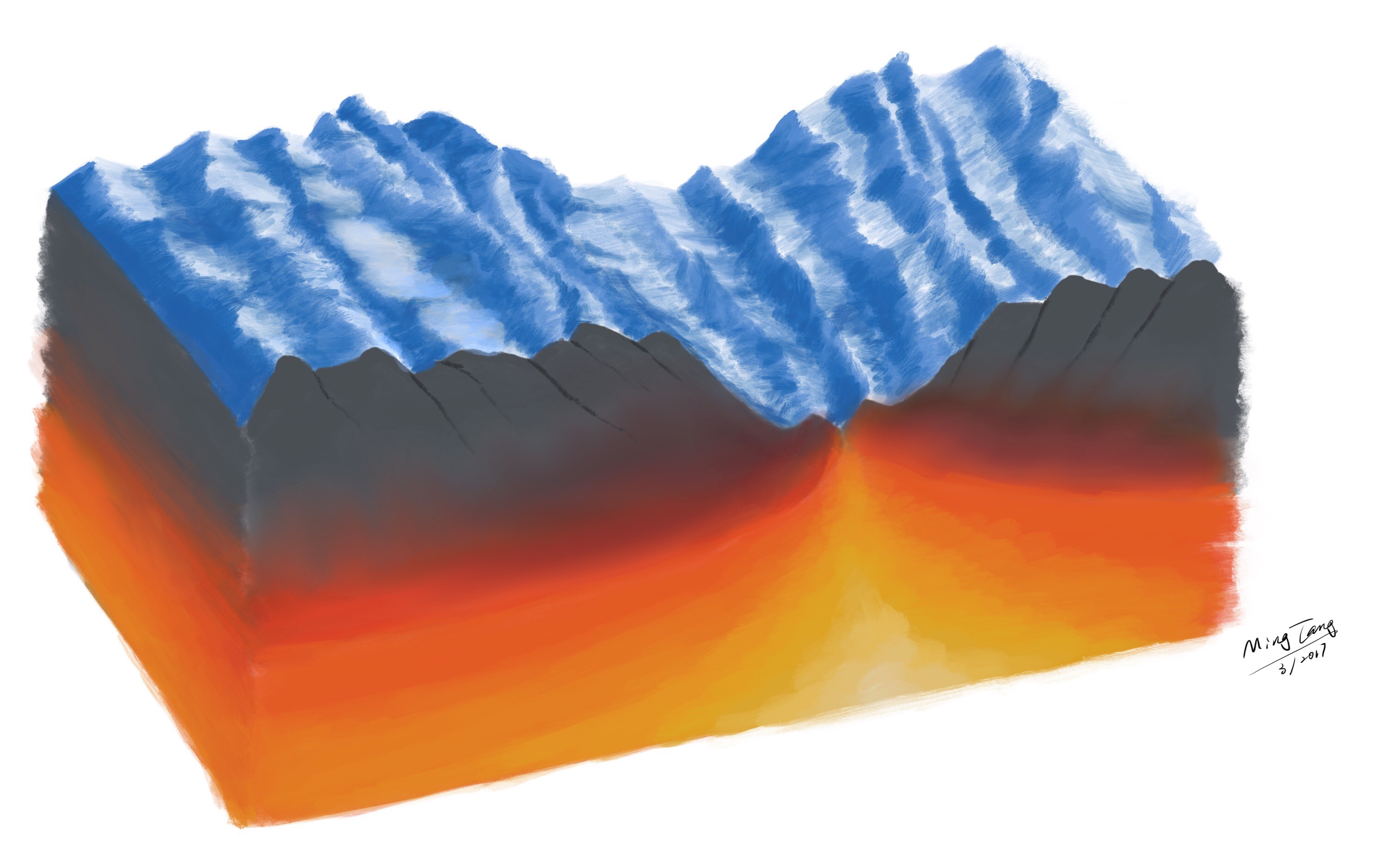

Fig. 1. Beneath mid ocean ridges, the mantle rises and melts, producing new oceanic crust.