Lower crust recycling — refining from beneath

How did Earth’s continental crust form?

A key feature of Earth’s continental crust is that it contains voluminous granites, and is thus felsic (rich in Si and Al). This crust is a distinctive product of our planet. The mantle melts to produce crust, but felsic composition of Earth’s continental crust means that it cannot be derived directly by melting the mantle, which is ultramafic (strongly enriched in Mg and Fe). After decades of research on this “paradox”, it has become clear that crustal recycling, perhaps following intra-crustal differentiation, is required to solve this composition problem. Several hypotheses have been proposed for changing the original crustal composition, including lower crustal recycling (gravitational sinking of denser crust initiaited by internal or external forces), upper crustal weathering followed by subduction of altered oceanic crust back into the mantle, subduction erosion and crustal subduction followed by relamination (rise of buoyant crustal materials), etc. Most of these processes have been observed, but the relative importance of each process in shaping the composition of the continental crust is uncertain, as is the question of whether or how these processes have changed over Earth history.

This project focused on data compilation, modeling, uncertainty evaluation and interpretation. For the first time, I realized that making significant contributions to science doesn’t always require collecting new data. It is worth going back to published data and re-evaluating them.

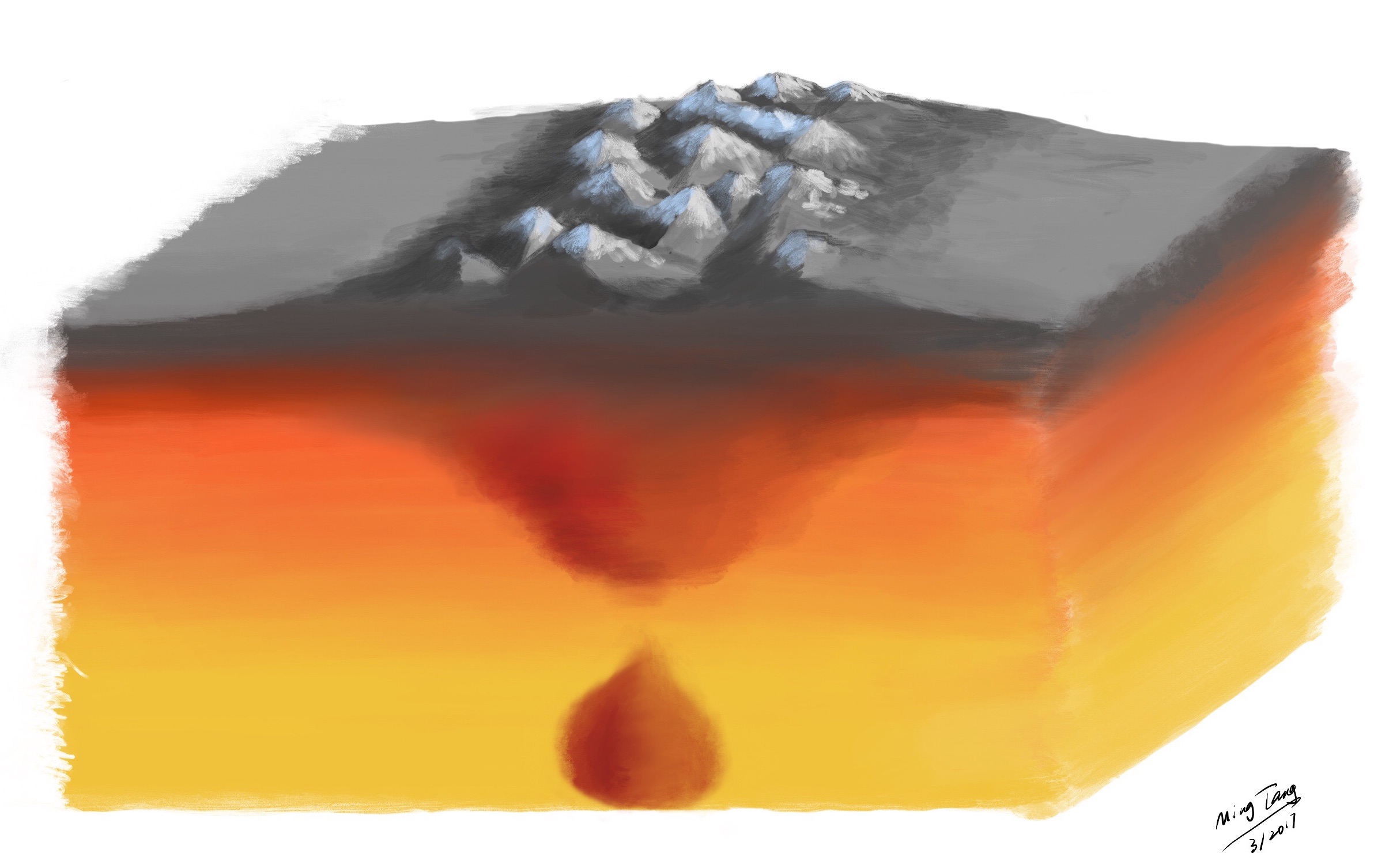

The lower part of the continental crust may transform to eclogite (essentially metamorphosed basalt) at high pressure during orogenic thickening processes. Eclogite is denser than peridotite, the main lithology in the underlying mantle, and thus the eclogitisized lower crust is gravitationally unstable and may sink into the mantle. This lower crustal recycling is one of the most important crustal recycling processes, but at the same time, it is poorly constrained because lower crust recycling is hard to observe directly. My contribution to this problem was to use the Eu anomaly to obtain a first-order estimate of the mass of the recycled lower continental crust through Earth’s history.

Europium anomaly is a term that describes the enrichment or depletion of Eu relative to the neighboring rare earth elements Sm and Gd. Europium is present in two valence states (+2 and +3) while Sm and Gd are only found in the +3 valence state. As magmas crystalize and differentiate in the crust, Eu is fractionated from Sm and Gd, as Eu2+ preferentially partitions into plagioclase (common white mineral in granites) while Sm and Gd (and Eu3+) tend to stay in the magmas. Plagioclase is a major rock-forming mineral in the crust. Plagioclase crystallizes out from magmas and settles down in the deep crust, forming cumulates together with other early-crystallizing minerals. Removal of plagioclase from a melt fractionates Eu from Sm and Gd, causing Eu depletion in the magma that ultimately ascends to the upper crust and Eu enrichment in the cumulate-rich lower crust. Therefore, removal of parts of the lower crust generates Eu depletion in the remaining crust, and the size of this depletion can be used to calculate the mass of recycled lower continental crust.

Following this method, I found the mass of the recycled lower continental crust was huge–about three times that of the remaining crust, that is, the continental crust we stand on today. In other words, nature produced four times by mass the modern continental crust and recycled 75% of it. This number has implications for a lot of geologic problems. For example, this large mass of recycled lower crust may form a significant geochemical region in the deep Earth, and may account for many of the elemental and isotopic imbalances observed in the crust-mantle system.

Fig. 1. A Rayleigh-Taylor type lower crust foundering beneath thickened crust in mountain belts.