The missing iron in Earth's continental crust

Iron (Fe) is one of the elements that we are most familiar with. It is a critical resource that drives modern civilization. We use things (partially) made of Fe everyday, from forks and spoons in the kitchen, cars on the road, frame structures of buildings, to rockets flying into space. Biologically, Fe is also an essential element. In our bodies, hemoglobin and myoglobin use Fe to form complexes with molecular oxygen. People who have deficiency of Fe may suffer from anaemia.

Indeed, Fe is very important, and the world would have been completely different without Fe. But, too much Fe can also be a disaster.

Iron has three valence states in most natural materials: 0, +2 and +3. The metallic Fe and Fe2+ are reduced, meaning oxygen-loving, and can react with oxygen to form Fe3+ — the oxidized, or rusty Fe. Within Earth’s interior, Fe is mostly in the 0 and +2 valence states. If these oxygen-loving Fe atoms/ions are transported to Earth’s surface, they may “eat” much of the oxygen in the atmosphere and kill most of the animals, including us, by anoxia.

Fig. 1. A colorized photo of the surface of Venus. It was taken by Russia’s Venera 13 spacecraft on March 1, 1982

Fig. 2. View of Mars surface photographed by the Curiosity Mars rover. Image credit: NASA, JPL.

Fortunately, Earth’s continental crust, which is the land we are living on, is depleted in Fe compared with the crusts of other rocky planets in the solar system and Earth’s low sitting ocean crust. The upper part of Earth’s continental crust has about 4% Fe by weight, while the surfaces of Venus and Mars have about 8% or more Fe. This already makes a huge difference, and even more interestingly, most of that 4% Fe in the rocks is already oxidized and will not react with oxygen in the atmosphere produced by photosynthesis!

Why is Earth’s continental crust depleted in Fe and so oxidized? How did this crust form? Why is Earth the only known rocky planet to have this type of crust? Why are we so special? Perhaps, without this Fe depleted crust, life forms like us could have never existed on Earth. For decades, geologists have been seeking to understand what causes Fe depletion in the formation of the continental crust.

Given the right conditions, Earth’s mantle can melt and produce magmas that rise and form crust when solidified. During its ascent, a magma gradually cools down and continuously crystallizes minerals. These minerals are usually denser than the magma and will sink. We call this process crystal fractionation. Because most of the crystallized minerals are compositionally different from the magma, the magma will keep changing its composition as it rises through the crust. Naturally, you might expect that those Fe depleted magmas must have crystallized some Fe rich minerals and dumped them during ascent. This is also what we geologists think, but the questions are what are those Fe rich minerals and under what conditions can they form?

Fig. 3. Mt. Shasta, an active volcano on the west coast of the US, and is predicted to erupt again. With an elevation of 4321.8 m, Mt. Shasta is one of the highest mountains in the US. Some of the magmas that erupted from Mt. Shasta are Fe depleted. I took this photo in the summer of 2017.

The lithosphere, which is the outer shell of Earth, is broken into multiple plates. Sometimes at plate boundaries, one plate gets cold and dense enough and subducts beneath another plate. Most of the Fe depleted magmas are found at these plate boundaries where subduction happens. In subduction zones, the subducting plate brings down a lot oxidized surface materials. These oxidized surface materials may contaminate the mantle and generate oxidized magmas. As these oxidized and wet magmas rise into the crust, an Fe rich mineral called magnetite may crystallize and cause Fe depletion in the magma. All these sound perfectly reasonable, and this magnetite hypothesis has been the dominant solution to the Fe depletion problem for decades. Indeed, we do see magnetite crystals in many oxidized, Fe depleted rocks.

However, there are some fundamental observations that this magnetite hypothesis cannot explain.

Not all subduction zone magmas are Fe depleted.

Back in the 1960s, a Japanese geologist, H. Kuno, found that in the Circum-Pacific volcanic belt, magmas become more Fe depleted from the ocean side toward the continent side. Today, we have more data and observations that support Kuno’s hypothesis 50 years ago, and what’s behind these observations is a crustal thickness control, that is, Fe depleted magmas are preferentially found in subduction zones built on thickened crust. For example, both Mariana arc in the west Pacific and Andean arc in the east Pacific are active subduction zones, but the crustal thickness differ significantly. In Mariana arc, the average crustal thickness is about 14 km while in Andean arc, especially the central part, the crust is thicker than 60-70 km. Mariana arc is dominated by Fe rich magmas whereas Andean arc is dominated by Fe depleted magmas. In effect, the composition of the Andean arc crust is much like that of the continental crust.

Why do Fe depleted, oxidized magmas like thickened crust? This is key to solving the mystery.

At the roots of thickened crust are rocks composed by the fractionated crystals, or the “dumped” minerals from magmas at great depths. Geologists call this type rocks cumulates. These cumulates are very dense, and are very rare at Earth’s surface. The reason that these cumulates do occasionally occur at the surface is that they may be accidentally brought up by some random but violent volcanic eruptions or some unusual tectonic processes. We were lucky to find some of these cumulate samples from Arizona, USA. Our cumulates formed at 60-80 km deep tens of millions years ago. These unusual samples tell the stories about what was happening in the deep crust that is otherwise largely inaccessible to us human beings.

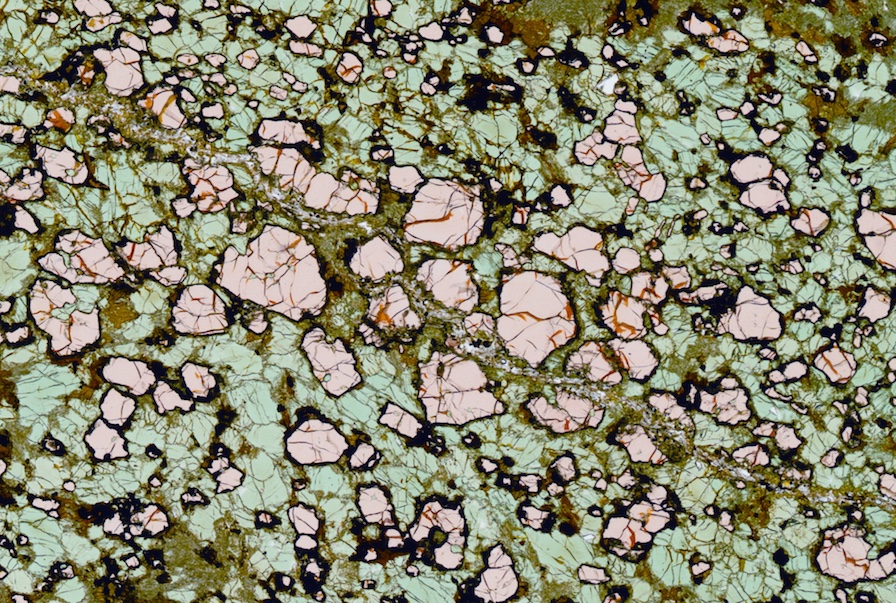

Fig. 4. A scanned image of our cumulate thin section. The pinkish minerals are garnets. They are up to 1mm in diameter. The greenish minerals are mostly clinopyroxene.

These deep cumulates are mostly composed of garnet and clinopyroxene, and are indeed rich in Fe! But magnetite doesn’t seem to be the most important Fe rich mineral. In fact, magnetite is absent in many of the cumulates. What else can carry so much Fe? Our attention was finally drawn by one of the major minerals in the cumulates—garnet. These garnets have up to ~18% Fe! Now everything starts to straighten up. Not all magmas can crystallize garnet. Garnet is only stable at high pressure and high water contents. This perfectly explains why Fe depleted magmas like thickened crust, or magmatic orogens, because magmas there are “capped” by a thick crust and therefore undergo crystal fractionation at high pressure. Only those magmas that go through thickened crust can crystallize garnet. An even more exciting thing about garnet is that garnet only takes Fe2+, so that its crystallization will increase the Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio in the magma. The oxidation state of a magma is mostly controlled by the average valence state of its Fe. So garnet crystallization will not only cause Fe depletion in the magma, but also oxidize the magma—the origin of the oxidized nature explained!

Fig. 5. Iron rich garnets from Alaska. These garnets are much bigger than the garnets we studied, and sometimes can reach gem quality. Garnet is also the birthstone of January.

Actually, this link between garnet and Fe depleted magmas was already noted by Trevor Green and Alfred Edward Ringwood in the 1960s. Ringwood is one of the fathers of modern petrology and geochemistry, and is highly respected. They found garnet phenocrysts in many Fe depleted magmas and carried out some experiments. Green and Ringwood published three papers on this topic from 1968-1972. Somehow, they didn’t continue in this direction, and this garnet model was forgotten by the community as the magnetite hypothesis became more and more popular. But it is really amazing that Green and Ringwood already thought about it 50 years ago! How much did we know about geology, about the continental crust, about subduction back in the 1960s? Even plate tectonics was just accepted by the scientific community at that time. They had far less data and knowledge about magma differentiation and crustal compositions, not to mention the rare deep cumulate samples that we have today.

Fig. 6. A.E.Ringwood (1930-1993), an Australian experimental geophysicist and geochemist. The mineral ringwoodite is named after him. Photo credit: Australian Academy of Science.

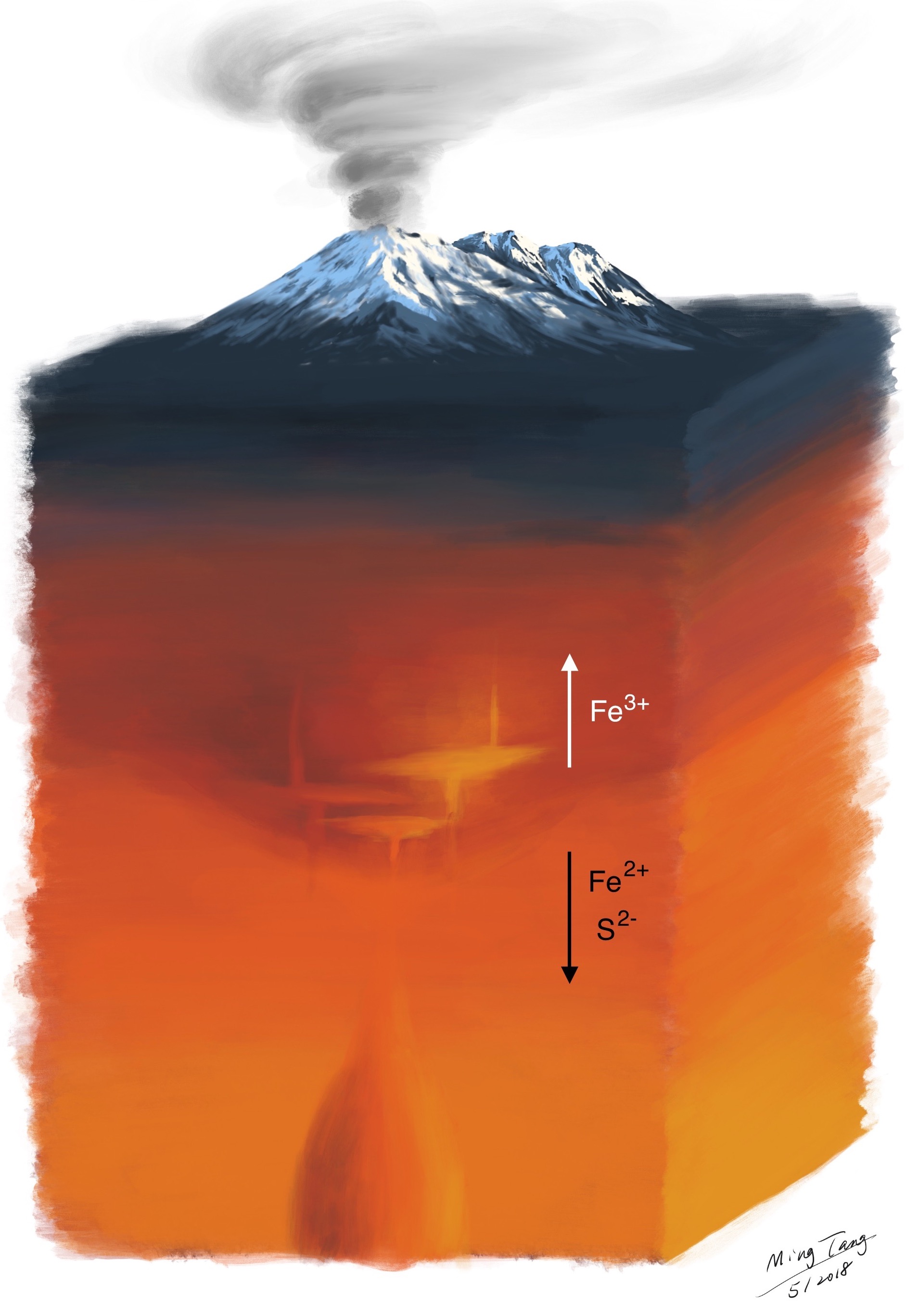

Nowadays, we may see the big pictures better than ever, thanks to big data geochemistry and those critical cumulate samples. Although nature is more complex than any single model can explain, this garnet hypothesis does seem to explain most of the observations in a self-consistent way. At the roots of the magmatic orogens, garnet keeps raining out from hot magmas coming up from the mantle. Like a filter, garnet crystallization changes the composition of the magma in the way that much of the oxygen-loving Fe2+ and toxic S2- are filtered out and locked in the deep crust, and will not make it to the surface with magmas. Garnet is dense, and it will not stay in the deep crust for long. Eventually, garnet will take all the Fe2+ and sulfides (S2- rich minerals) with it and sink into Earth’s deeper interior. Without garnet, Earth’s surface, including the atmosphere, might have been completely different. Free oxygen molecules may have never accumulated to the levels to sustain complicated life forms like us.

If this garnet hypothesis were correct, magmatic orogens, such as Andes where high altitude giant volcanos are typically seen, would be the primary factories of Earth’s continents. Just about every piece of the continental crust, our homeland, was born in such a violent and magnificent way. Today, we don’t see most of the mountains across the continents because they have been eroded away, but the Fe depleted nature of the crust preserves the memories of its past millions to billions of years ago.

Fig. 7. Cartoon illustrating garnet crystallization at the root of magmatic orogens, pulling the reducing Fe2+ and S2- out of the magmas. Cartoon not to scale.