Li diffusion mechanism in zircon—the masterpiece of my Ph.D. research

This is the project that I originally proposed for my Ph.D. dissertation, although I ended up doing multiple projects that interested me. To solve the problem, I teamed up with people from multiple institutions. This project has given me the opportunities to operate state-of-the-art instruments and conduct high-temperature experiments. I traveled a lot to do the analyses and experiments, and this allowed me to visit many great places across the country.

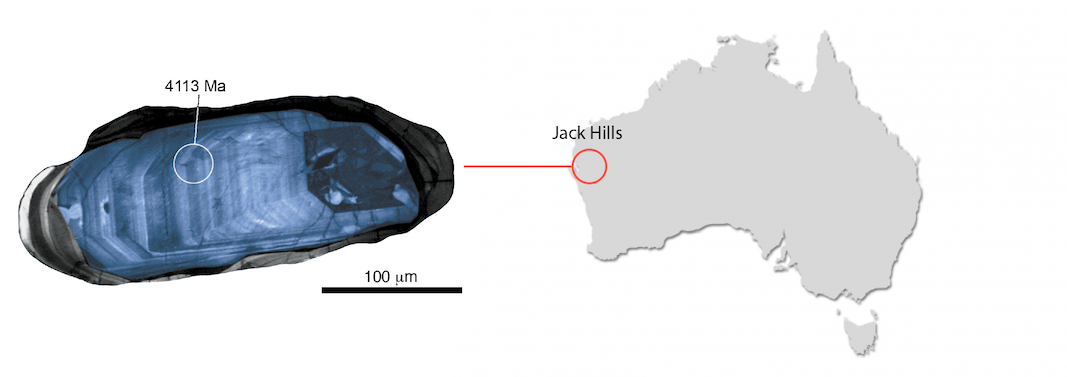

Fig. 1. A zircon from the Jack Hills, Australia. The Jack Hills zircons, many of which are > four billion years old, are the oldest known materials on Earth. The false-colord microscope zircon cathodoluminescence image is from Mary Diman and John Valley (UW-Madison).

I got interested in Li diffusion in zircon because of the extremely light Li isotopes reported in the Hadean zircons—Earth’s oldest known materials. The light Li isotope composition was interpreted to reflect intense chemical weathering of Earth’s crust four billion years ago. However, such light Li isotopes can also be explained by Li diffusion in zircon. So I decided to study Li diffusion in zircon.

My current results suggest that Li diffusion in zircon is a common process. On the other hand, the sharp Li concentration zoning seen in many zircons and Li diffusion in the direction of increasing concentration indicate multiple modes of Li diffusion in zircon. Our observations can be explained if Li strongly couples with REE and Y in zircon. These observations have important implications for people who want to use Li isotopes in zircon to track chemical weathering in the past, or to use Li isotopes as a geospeedometer to constrain the duration of geologic processes or the maximum temperature in metamorphic/igneous processes.

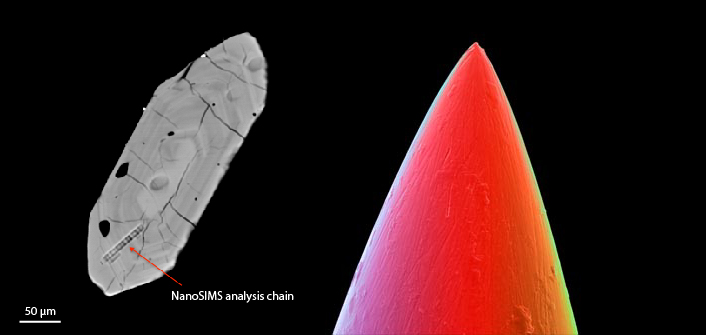

Fig. 2. On the left is a backscattered image showing the track of NanoSIMS analyses on of one my zircon crystals. This chain analysis consists of 30 spot analyses across ~50 µm. On the right, a microscope image of a needle tip (from web) is shown to provide the reader a sense of the scale.

Simulated diffusion-growth profiles for one of the zircons I studied.

There are many challenges in this project, not the least of which was to measure Li isotope ratios in my zircon samples. Here I list some numbers to give the reader some sense of the analytical challenge. Zircons are ~200 µm in size; I needed to measure Li isotopes at ~ 1 µm spatial resolution, and 20−40 spot analyses along 50 µm profiles without overlapping; typical Li concentrations in natural zircons range from a few ppm (10-6, or parts per million by weight) to less than 1 ppm; Li isotope ratios, 7Li/6Li, need to be measured to permil (0.001) level of precision to be useful.

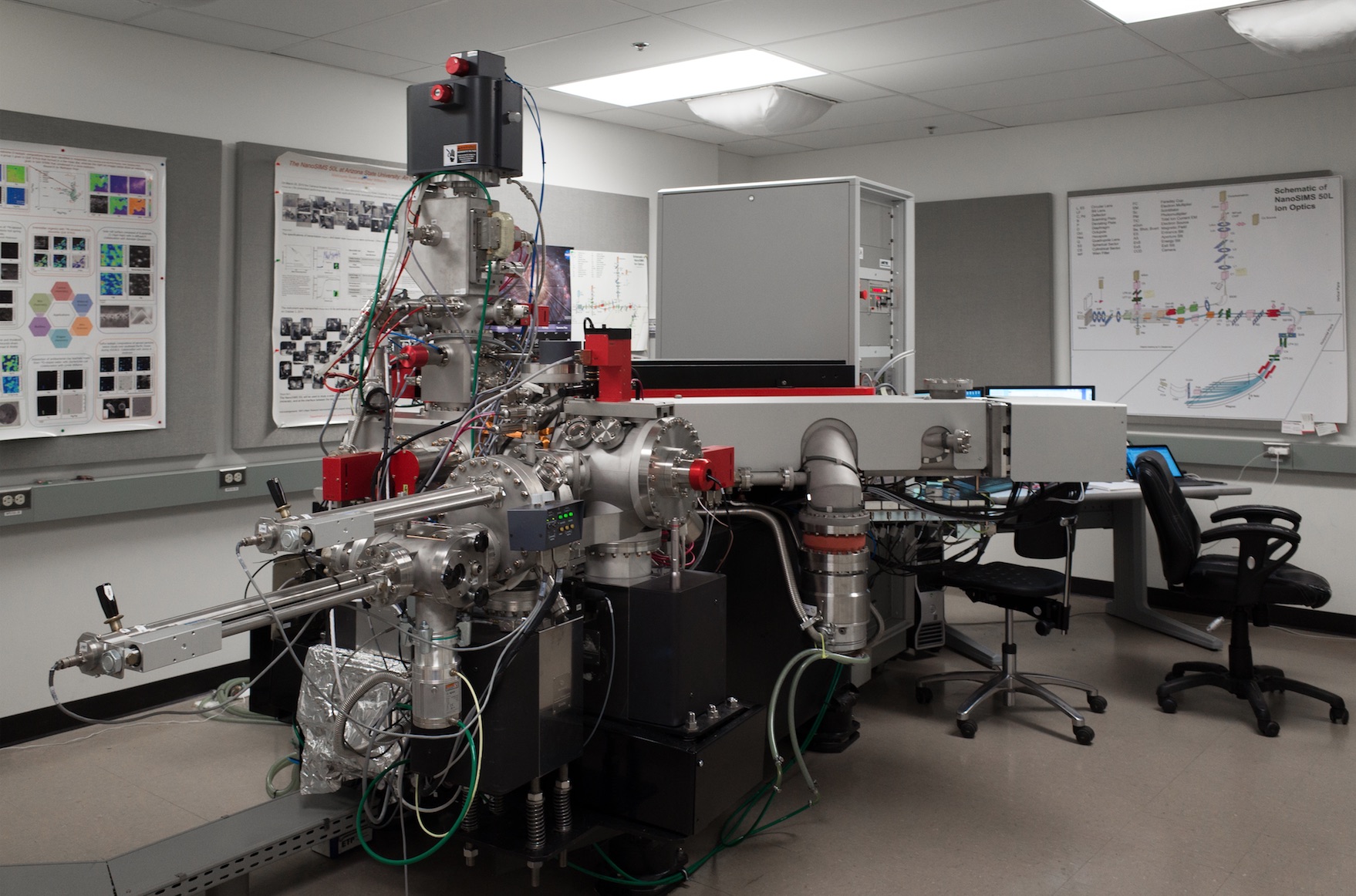

I was at first rejected by the NanoSIMS lab in Beijing when I reached out to them to do the analyses. They told me my analyses were technically impossible. I ended up measuring my samples at Arizona State University, in collaboration with Dr. Maitrayee Bose. We found the measurements to be possible, but only after the instrument was tuned to extreme performance. During my four two-week long trips to ASU, two generated zero useful data, and much of the third one was about troubleshooting and tuning.

Fig. 3. The NanoSIMS lab at the Arizona State University. I’ve been working in this lab for a total of ~1000 hours over the last three years. NanoSIMS is tough to use, but it is the only instrument on this planet that meets the requirements of my analyses.

We were proud to be the first ones to be able to measure Li isotopes in zircon by NanoSIMS. We achieved this because we didn’t give up, and much of the credit goes to Maitrayee. As her colleague Lynda Williams said, “Maitrayee is always optimistic, so we have good karma!”. Be positive, and things will work out, as my advisor Bill McDonough always encourages me.