The source of elemental fractionation in LA-ICP-MS analysis

Some of my Ph.D. projects were analytically challenging, which required measurements of either high precision or extremely small sample sizes (e.g., ~10-17 g). These challenges drove me to study the instruments—how they work and how to optimize them for my research purposes.

Generally, there are two important sources of error in instrumental analysis. One is related to counting statistics, or the number of observations, which largely depends on sample sizes; the other one can be caused by many factors including electronic noise from the instruments, fractionation during analysis, operation conditions, etc. I was most concerned with the elemental and isotopic fractionation during my LA-ICP-MS (laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry) analysis, a technique that is widely used in geoscience, including my MORB Eu anomaly project.

What’s causing the elemental/isotopic fractionation during LA-ICP-MS analysis?

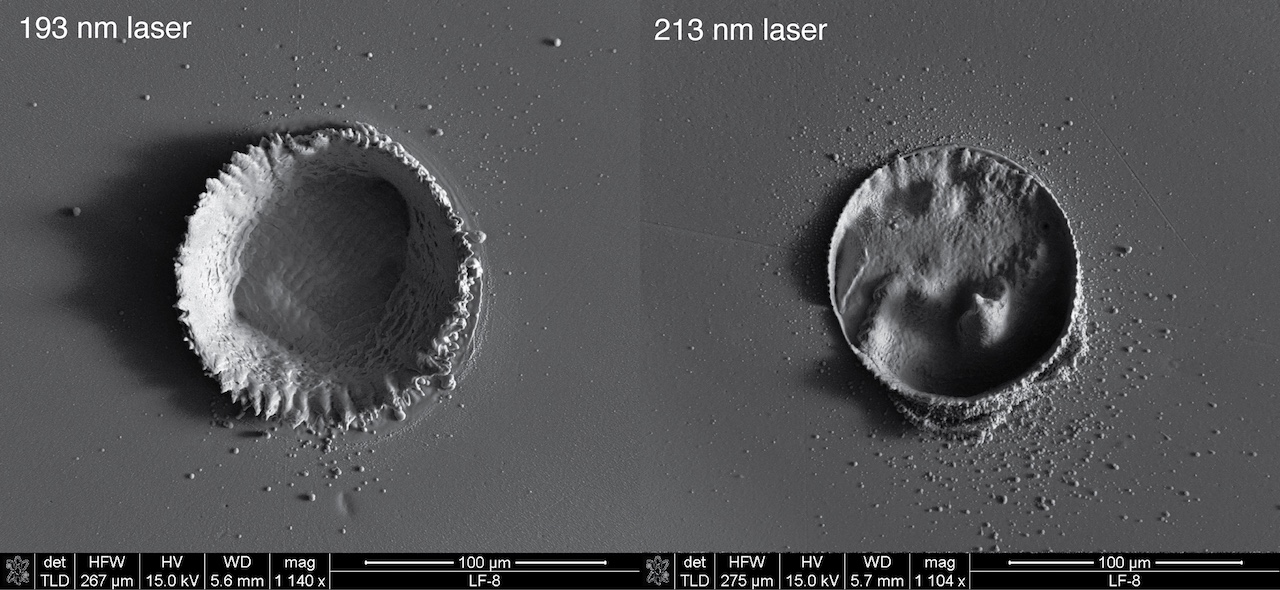

Fig. 1. SEM images of craters on brass produced by lasers of two wavelengths—193 nm and 213 nm.

LA-ICP-MS analysis uses a laser ablation instrument as a sample introduction system. A pulsed laser beam hits the sample surface, causes dissociation and releases ions, electrons, neutral particles, etc. These released materials, with further interaction with the incoming laser beam, forms a plasma right above the sample. The plasma then cools and condenses, forming particles of nanometer to micrometer sizes. At this stage, the released sample becomes an aerosol, which is then transported to the ICP-MS for ionization and analysis.

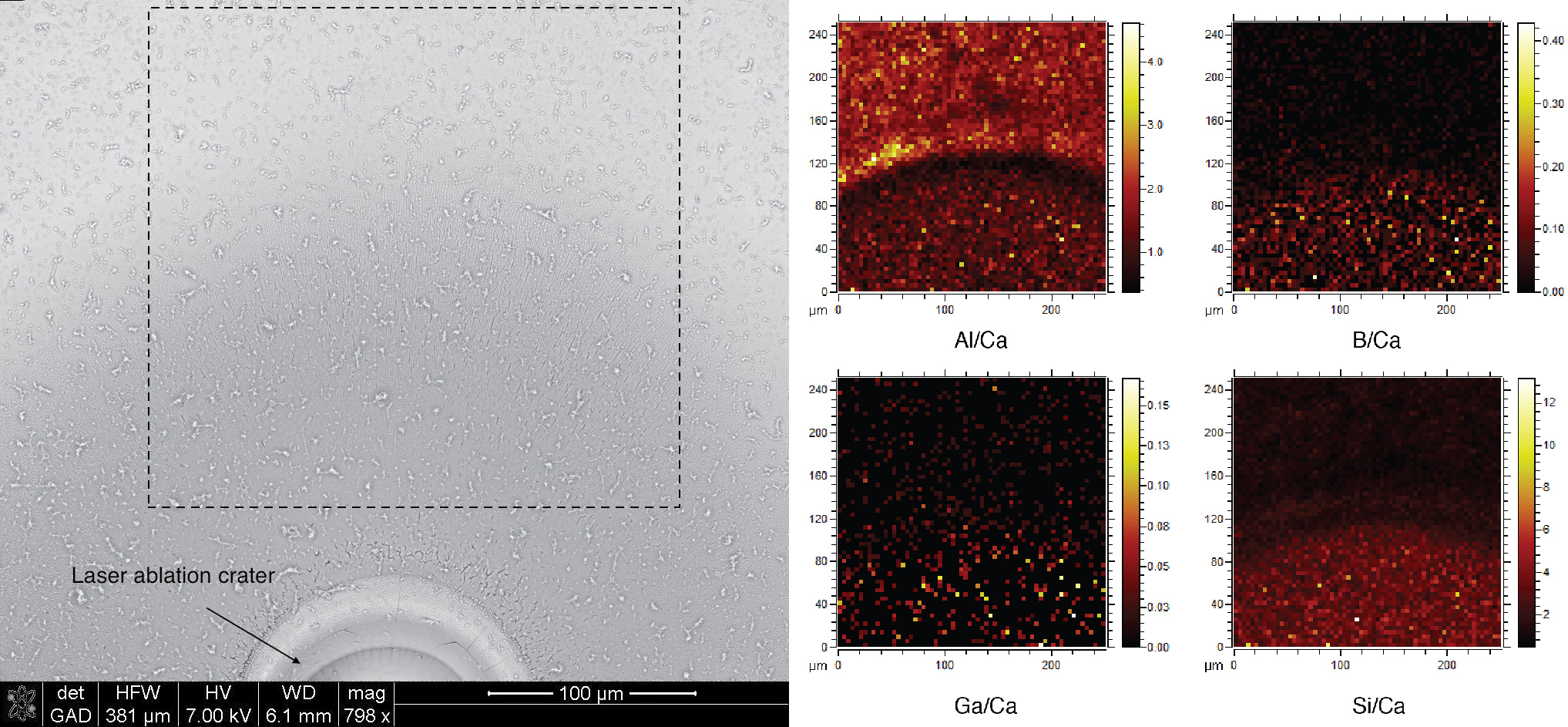

Fig. 2. On the left is a SEM image showing the condenstation blanket around a laser crater. On the right are some ion imaging results measured by Time of Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer (ToF-SIMS). These ToF-SIMS images show the composition change across the condensation blanket.

It turns out that not all particles in the aerosol can be transported to the ICP-MS or completely dissociated and converted to ions in the ICP. Particles close to or larger than 1 um size usually have problems here. If particles of different sizes have different compositions, then one will not get an accurate composition for the sample from the ICP-MS end. To test this “if”, I studied the condensation blanket around the crater, which forms by aerosol particle precipitation. Indeed, the condensation blanket changes its composition as a function of the distance to the ablation crater.

I also did a lot of experiments with the laser ablation system by changing the ablation crater geometry, laser beam size, He gas flow rate, etc. I connected the the laser ablation system to a particle counter to measure the number of particles of different sizes. I found that all these parameters can influence the size distribution of the particles transported to the ICP-MS. Generally, small laser beams produce small particles; deep ablation produces small particles.

These projects wouldn’t have been possible without Rick Arevalo’s help. Rick was my advisor Bill McDonough’s former student. It turned out that my findings are not in the favor of Rick’s work. Once, Rick, Bill and I were sitting together, discussing my results and the manuscript. Bill was joking “We can just write the title as Rick Arevalo was wrong! Hahaha…”. In spite of these hard-to-swallow findings, Rick was always helping me, from sample preparation to the operation of LA-ICP-MS. It was also Rick who borrowed a particle counter so that we could measure the particle size distribution—a key step in my experiments. Rick has my respect.